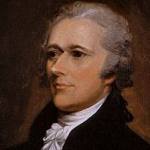

Alexander Hamilton was a Founding Father, soldier, economist, political philosopher, one of America’s first constitutional lawyers and the first United States Secretary of the Treasury.

Alexander Hamilton: The Works of Alexander Hamilton, Volume 4

Foreign Relations, Cabinet Paper: Hamilton to Thomas Jefferson, March, 1792

March, 1792

Mr. Hamilton presents his respectful compliments to the Secretary of State. He has perused, with as much care and attention as time has permitted, the draft of a letter in answer to that of Mr. Hammond, of March 5th.2

Much strong ground has been taken, and strongly maintained, particularly in relation to:

The recommendatory clauses of the treaty;

The previous infractions by Great Britain, as to negroes and posts;

The question of interest.

And many of the suggestions of the British Minister, concerning particular acts and adjudications, as far as can be judged without consulting the documents, appear to be satisfactorily obviated.

But doubts arise in the following particulars:

1st. The expediency of the retaliation on the 1st, 2d, and 3d pages. Much of the propriety of what is said depends on the question of the original right or wrong of the war. Should it lead to observations on that point, it may involve an awkward and irritating discussion. Will it not be more dignified, as well as more discreet, to observe, concisely and generally, on the impropriety of having deduced imputations from transactions during the war, and (alluding in the aggregate, and without specification, to the instances of legislative warfare on the part of the British Parliament which might be recriminated) to say that this is foreborne, as leading to an unprofitable and unconciliating discussion?

2d. The soundness of the doctrine (page 4), that all governmental acts of the States prior to the 11th of April are out of the discussion. Does not the term “subjects,” to whom, according to Vatel, notice is necessary, apply merely to individuals? Are not States members of the federal league, the parties contractantes, “who are bound by the treaty itself, from the time of its conclusion; that is, in the present case, from the time the provisional treaty took effect, by the ratification of the preliminary articles between France and Britain?”

3d. The expediency of so full a justification of the proceedings of certain States with regard to debts. In this respect extenuation rather than vindication would seem to be the desirable course. It is an obvious truth, and is so stated, that Congress alone has the right to pronounce a breach of the treaty, and to fix the measure of retaliation. Not having done it, the States which undertook the task for them, contravened both their federal duty and the treaty. Do not some of the acts of Congress import that the thing was viewed by that body in this light? Will it be well for the Executive now to implicate itself in too strong a defence of measures which have been regarded by a great proportion of the Union, and by a respectable part of the citizens of almost every State, as exceptionable in various lights? May not too earnest an apology for instalment and paper-money laws, if made public hereafter, tend to prejudice, somewhat, the cause of good government, and, perhaps, to affect disadvantageously the character of the general government?To steer between too much concession and too much justification in this particular, is a task both difficult and delicate; but it is worthy of the greatest circumspection to accomplish it.

4th. The expediency of risking the implication of the tacit approbation of Congress of the “retaliations of four States” by saying that they neither gave nor refused their sanction to those retaliations. Will not the national character stand better if no ground to suspect the connivance of the national government is afforded? Is it not the fact that Congress were inactive spectators of the infractions which took place, because they had no effectual power to control them?

5th. The truth of the position, which seems to be admitted (page 57), that the quality of alien enemy subsisted till the definitive treaty. Does not an indefinite cessation of hostilities, founded too on a preliminary treaty, put an end to the state of war, and consequently destroy the relation of alien enemy?The state of war may or may not revive if points which remain to be adjusted by a definitive treaty are never adjusted by such a treaty; but it is conceived that a definitive treaty may never take place, and yet the state of war and all its consequences be completely terminated.

6th. The expediency of grounding any argument on the supposition of either party being in the wrong (as in page 65). The rule in construing treaties is to suppose both parties in the right, for want of a common judge, etc. And a departure from this rule in argument might possibly lead to unpleasant recrimination.

The foregoing are the principal points that have occurred on one perusal. They are submitted without reserve. Some lesser matters struck, which would involve too lengthy a commentary; many of them merely respecting particular expressions. A mark + is in the margin of the places, which will probably suggest to the Secretary of State, on revision, the nature of the reflections which may have arisen. It is imagined that there is a small mistake in stating that Waddington paid no rent.2

Endnotes

1 Jefferson’s answer to Hammond’s letter of March 5th, although he appears to have consulted Hamilton in regard to it during the same month, was not sent until May 29, 1792. It was long, able, and elaborate.—See Jefferson’s Works, ⅲ., 365.

2 Jefferson accepted and adopted Hamilton’s suggestions in all except the second and third objections. See Hamilton’s Works, J. C. Hamilton edition, ⅵ., p. 144, Jefferson to Hamilton, March, 1791, a letter not found in Jefferson’s Works. Both Hamilton’s letter and Jefferson’s reply are misdated by J. C. Hamilton. Hammond did not arrive until the autumn of 1791, and this letter was written in March, 1792, not 1791, as J. C. Hamilton has it.